LinkedIn’s AutoFill plugin could leak user data, secret fix failed

Facebook isn’t the only one in the hot seat over data privacy. A flaw in LinkedIn’s AutoFill plugin that websites use to let you quickly complete forms could have allowed hackers to steal your full name, phone number, email address, ZIP code, company and job title. Malicious sites have been able to invisibly render the plugin on their entire page so if users who are logged into LinkedIn click anywhere, they’d effectively be hitting a hidden “AutoFill with LinkedIn” button and giving up their data.

Researcher Jack Cable discovered the issue on April 9th, 2018 and immediately disclosed it to LinkedIn. The company issued a fix on April 10th but didn’t inform the public of the issue. Cable quickly informed LinkedIn that its fix, which restricted the use of its AutoFill feature to whitelisted sites who pay LinkedIn to host their ads, still left it open to abuse. If any of those sites have cross-site scripting vulnerabilities, which Cable confirmed some do, hackers can still run AutoFill on their sites by installing an iframe to the vulnerable whitelisted site. He got no response from LinkedIn over the last nine days, so Cable reached out to TechCrunch.

LinkedIn’s AutoFill tool

LinkedIn tells TechCrunch it doesn’t have evidence that the weakness was exploited to gather user data. But Cable says “it is entirely possible that a company has been abusing this without LinkedIn’s knowledge, as it wouldn’t send any red flags to LinkedIn’s servers.”

I demoed the security fail on a site Cable set up. It was able to show me my LinkedIn sign-up email address with a single click anywhere on the page, without me ever knowing I was interacting with an exploited version of LinkedIn’s plugin. Even if users have configured their LinkedIn privacy settings to hide their email, phone number or other info, it can still be pulled in from the AutoFill plugin.

“It seems like LinkedIn accepts the risk of whitelisted websites (and it is a part of their business model), yet this is a major security concern,” Cable wrote to TechCrunch. [Update: He’s now posted a detailed write-up of the issue.]

A LinkedIn spokesperson issued this statement to TechCrunch, saying it’s planning to roll out a more comprehensive fix shortly:

We immediately prevented unauthorized use of this feature, once we were made aware of the issue. We are now pushing another fix that will address potential additional abuse cases and it will be in place shortly. While we’ve seen no signs of abuse, we’re constantly working to ensure our members’ data stays protected. We appreciate the researcher responsibly reporting this and our security team will continue to stay in touch with them.

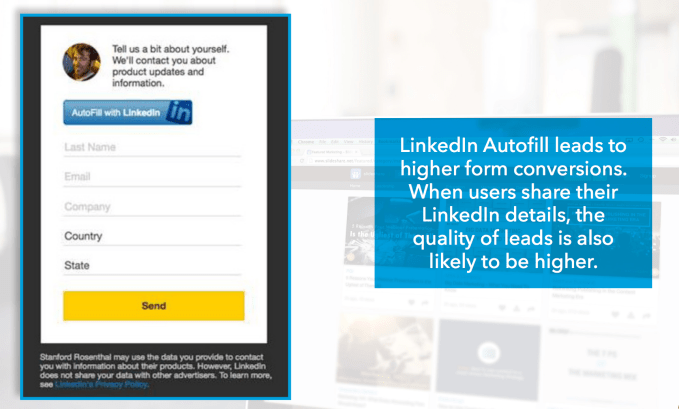

For clarity, LinkedIn AutoFill is not broadly available and only works on whitelisted domains for approved advertisers. It allows visitors to a website to choose to pre-populate a form with information from their LinkedIn profile.

Facebook has recently endured heavy scrutiny regarding data privacy and security, and just yesterday confirmed it was investigating an issue with unauthorized JavaScript trackers pulling in user info from sites using Login With Facebook.

But Cable’s findings demonstrate that other tech giants deserve increased scrutiny too. In an effort to colonize the web with their buttons and gather more data about their users, sites like LinkedIn have played fast and loose with people’s personally identifiable information.

The research shows how relying on whitelists of third-party sites doesn’t always solve a problem. All it takes is for one of those sites to have its own security flaw, and a bigger vulnerability can be preyed upon. More than 70 of the world’s top websites were on LinkedIn’s whitelist, including Twitter, Stanford, Salesforce, Edelman and Twilio. OpenBugBounty shows the prevalence of cross-site scripting problems. These “XSS” vulnerabilities accounted for 84 percent of security flaws documented by Symantec in 2007, and bug bounty service HackerOne defines XSS as a massive issue to this day.

With all eyes on security, tech companies may need to become more responsive to researchers pointing out flaws. While LinkedIn initially moved quickly, its attention to the issue lapsed while only a broken fix was in place. Meanwhile, government officials considering regulation should focus on strengthening disclosure requirements for companies that discover breaches or vulnerabilities. If they know they’ll have to embarrass themselves by informing the public about their security flaws, they might work harder to keep everything locked tight.