Ebola 101: Answers to your questions about causes, symptoms, transmission and treatments

The deadly Ebola virus is snatching headlines once again as the Democratic Republic of Congo faces its ninth outbreak since its discovery more than four decades ago.

Here’s what you need to know about the deadly disease.

What is Ebola?

Ebola hemorrhagic fever is a disease with a high fatality rate that most commonly affects people and nonhuman primates such as monkeys, gorillas and chimpanzees, according to the World Health Organization.

The fever is caused by an infection with one of five known Ebola virus species: Zaire ebolavirus, Bundibugyo ebolavirus, Sudan ebolavirus, Taï Forest ebolavirus (formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus) and Reston ebolavirus. Four of the strains can cause severe illness in humans and animals. The fifth, Reston virus, has caused illness in some animals, but not in humans.

The current outbreak in Congo is due to the Zaire ebolavirus, which has the highest mortality rate, ranging from 60% to 90%, according to the World Health Organization.

Where did the Ebola virus come from?

The virus is named after the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the virus was first recognized in 1976, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The first human outbreaks occurred that same year, one in northern Zaire, now Democratic Republic of Congo, which is in central Africa. The other was in southern Sudan, now South Sudan, which is adjacent to Congo.

Fatal Ebola outbreaks among humans have been confirmed in the following countries over the last few decades: Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, South Sudan, Ivory Coast, Uganda, Republic of Congo, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

What are the symptoms of Ebola hemorrhagic fever?

Symptoms of Ebola typically include weakness, fever, aches, diarrhea, vomiting and stomach pain, which are common enough to be thought of as flu or malaria at first. Some patients also experience a rash around the face, neck, trunk, and arms usually appearing by day five or seven, red eyes, chest pain, throat soreness, difficulty breathing or swallowing and bleeding (including internal). Usually, massive hemorrhage, especially in the gastrointestinal system, occurs only in fatal cases.

Typically, symptoms appear eight to 10 days after exposure to the virus, but the incubation period can span two to 21 days.

How easy is it to catch Ebola?

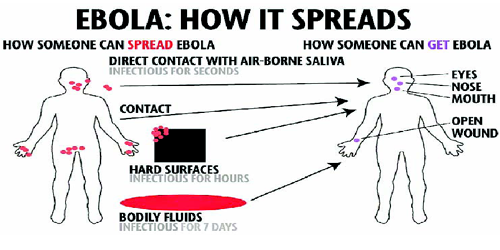

Scientists say Ebola is extremely infectious but not extremely contagious. Because an infinitesimally small amount of the virus can cause illness, it is considered extremely infectious. However, because the virus is not transmitted through the air, it is considered “moderately” contagious.

How do people catch Ebola?

Humans can be infected by other humans if they come into contact with body fluids such as blood, urine and tears from an infected person or contaminated objects from an infected person. Unprotected health care workers are susceptible to infection because of their close contact with patients during treatment.

Ebola is not transmissible if someone is asymptomatic and usually not after someone has recovered from it. However, the virus has been found in semen for up to three months, and “possibly” is transmitted from contact with that semen, according to the CDC.

Humans can also be exposed to the virus through infected animals, for example, by butchering them.

Which animals carry the Ebola virus?

Researchers believe the most likely natural hosts are fruit bats, though the exact reservoir of Ebola viruses is still unknown. In addition to fruit bats, other animals that have been known to become infected with the virus are chimpanzees, gorillas, monkeys, forest antelope and porcupines.

What is the death rate?

The average case fatality rate for Ebola virus disease is about 50%, though this rate has varied from 25% to 90% during past outbreaks. A patient’s chance of survival depends, in part, on the particular subtype of ebolavirus and access to care.

How is Ebola diagnosed?

In the early stages, diagnosis is difficult since Ebola can be difficult to distinguish from malaria, typhoid fever, meningitis, yellow fever and other infectious diseases. A preliminary diagnosis may be based on symptoms combined with travel and exposure history, but a positive laboratory blood test is needed as confirmation.

How is Ebola treated?

The methods used to treat Ebola patients include quarantine and early care using oral or intravenous fluids for rehydration, according to the WHO. While no licensed treatments have been proven capable of neutralizing the virus, a range of therapies are under development, including immune therapies and drug therapies.

Dr. Daniel R. Lucey, a spokesman for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and an adjunct professor of medicine-infectious diseases at Georgetown University Medical Center, explained that ZMapp, an immune-based antibody treatment that can be given to people who are already sick with Ebola, is one such experimental treatment.

Also among the experimental treatments that have shown some promise is favipiravir, a broad-spectrum antiviral drug, one that is intended to treat a range of viruses.

Patients have also been given plasma donations from the blood of Ebola survivors to boost the body’s immune response. This too is experimental.

And drugs for HIV, multiple sclerosis, influenza and other illnesses have also been tried. None of the trials, however seemed to show a definitive cure.

Is there an Ebola vaccine?

Lucey said that “there are quite a few experimental vaccines, both from the West and from China and from Russia,” yet only one investigational Ebola vaccine is being used in the current outbreak — recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-Zaire Ebola virus (or rVSV-ZEBOV), made by pharmaceutical giant Merck.

According to WHO, the experimental Ebola vaccine proved “highly protective” against the deadly virus during a study conducted in Guinea during the 2013-2015 outbreak in West Africa. Among the nearly 6,000 people who received the vaccine at that time, no Ebola cases were recorded 10 days or more after vaccination.

The vaccine “can never cause Ebola,” explained Lucey. “It is given on a voluntary basis through informed consent and it has been approved by the DRC ethics committee as well as the regulatory committee.”

Merck donated thousands of doses to WHO and anticipates filing for licensure and approval by regulatory agencies next year, said Pam Eisele, a company spokeswoman. Licensure, if granted, would allow the company to market the vaccine.

* Source: CNN

The post Ebola 101: Answers to your questions about causes, symptoms, transmission and treatments appeared first on Vanguard News.