How did Thumbtack win the on-demand services market?

Earlier today, the services marketplace Thumbtack held a small conference for 300 of its best gig economy workers at an event space in San Francisco.

For the nearly ten-year-old company the event was designed to introduce some new features and a redesign of its brand that had softly launched earlier in the week. On hand, in addition to the services professionals who’d paid their way from locations across the U.S. were the company’s top executives.

It’s the latest step in the long journey that Thumbtack took to become one of the last companies standing with a consumer facing marketplace for services.

Back in 2008, as the global financial crisis was only just beginning to tear at the fabric of the U.S. economy, entrepreneurs at companies like Thumbtack andTaskRabbit were already hard at work on potential patches.

This was the beginning of what’s now known as the gig economy. In addition to Thumbtack and TaskRabbit, young companies like Handy, Zaarly, and several others — all began by trying to build better marketplaces for buyers and sellers of services. Their timing, it turns out, was prescient.

In snowy Boston during the winter of 2008, Kevin Busque and his wife Leah were building RunMyErrand, the marketplace service that would become TaskRabbit, as a way to avoid schlepping through snow to pick up dog food.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, Marco Zappacosta, a young entrepreneur whose parents were the founders of Logitech, and a crew of co-founders including were building Thumbtack, a professional services marketplace from a home office they shared.

As these entrepreneurs built their businesses in northern California (amid the early years of a technology renaissance fostered by patrons made rich from returns on investments in companies like Google and Salesforce.com), the rest of America was stumbling.

In the two years between 2008 and 2010 the unemployment rate in America doubled, rising from 5% to 10%. Professional services workers were hit especially hard as banks, insurance companies, realtors, contractors, developers and retailers all retrenched — laying off staff as the economy collapsed under the weight of terrible loans and a speculative real estate market.

Things weren’t easy for Thumbtack’s founders at the outset in the days before its $1.3 billion valuation and last hundred plus million dollar round of funding. “One of the things that really struck us about the team, was just how lean they were. At the time they were operating out of a house, they were still cooking meals together,” said Cyan Banister, one of the company’s earliest investors and a partner at the multi-billion dollar venture firm, Founders Fund.

“The only thing they really ever spent money on, was food… It was one of these things where they weren’t extravagant, they were extremely purposeful about every dollar that they spent,” Banister said. “They basically slept at work, and were your typical startup story of being under the couch. Every time I met with them, the story was, in the very early stages was about the same for the first couple years, which was, we’re scraping Craigslist, we’re starting to get some traction.”

The idea of powering a Craigslist replacement with more of a marketplace model was something that appealed to Thumbtack’s earliest investor and champion, the serial entrepreneur and angel investor Jason Calcanis.

Thumbtack chief executive Marco Zappacosta

“I remember like it was yesterday when Marco showed me Thumbtack and I looked at this and I said, ‘So, why are you building this?’ And he said, ‘Well, if you go on Craigslist, you know, it’s like a crap shoot. You post, you don’t know. You read a post… you know… you don’t know how good the person is. There’re no reviews.'” Calcanis said. “He had made a directory. It wasn’t the current workflow you see in the app — that came in year three I think. But for the first three years, he built a directory. And he showed me the directory pages where he had a photo of the person, the services provided, the bio.”

The first three years were spent developing a list of vendors that the company had verified with a mailing address, a license, and a certificate of insurance for people who needed some kind of service. Those three features were all Calcanis needed to validate the deal and pull the trigger on an initial investment.

“That’s when I figured out my personal thesis of angel investing,” Calcanis said.

“Some people are market based; some people want to invest in certain demographics or psychographics; immigrant kids or Stanford kids, whatever. Mine is just, ‘Can you make a really interesting product and are your decisions about that product considered?’ And when we discuss those decisions, do I feel like you’re the person who should build this product for the world And it’s just like there’s a big sign above Marco’s head that just says ‘Winner! Winner! Winner!'”

Indeed, it looks like Zappacosta and his company are now running what may be their victory lap in their tenth year as a private company. Thumbtack will be profitable by 2019 and has rolled out a host of new products in the last six months.

Their thesis, which flew in the face of the conventional wisdom of the day, was to build a product which offered listings of any service a potential customer could want in any geography across the U.S. Other companies like Handy and TaskRabbit focused on the home, but on Thumbtack (like any good community message board) users could see postings for anything from repairman to reiki lessons and magicians to musicians alongside the home repair services that now make up the bulk of its listings.

“It’s funny, we had business plans and documents that we wrote and if you look back, the vision that we outlined then, is very similar to the vision we have today. We honestly looked around and we said, ‘We want to solve a problem that impacts a huge number of people. The local services base is super inefficient. It’s really difficult for customers to find trustworthy, reliable people who are available for the right price,'” said Sander Daniels, a co-founder at the company.

“For pros, their number one concern is, ‘Where do I put money in my pocket next? How do I put food on the table for my family next?’ We said, ‘There is a real human problem here. If we can connect these people to technology and then, look around, there are these global marketplace for products: Amazon, Ebay, Alibaba, why can’t there be a global marketplace for services?’ It sounded crazy to say it at the time and it still sounds crazy to say, but that is what the dream was.”

Daniels acknowledges that the company changed the direction of its product, the ways it makes money, and pivoted to address issues as they arose, but the vision remained constant.

Meanwhile, other startups in the market have shifted their focus. Indeed as Handy has shifted to more of a professional services model rather than working directly with consumers and TaskRabbit has been acquired by Ikea, Thumbtack has doubled down on its independence and upgrading its marketplace with automation tools to make matching service providers with customers that much easier.

Late last year the company launched an automated tool serving up job requests to its customers — the service providers that pay the company a fee for leads generated by people searching for services on the company’s app or website.

Thumbtack processes about $1 billion a year in business for its service providers in roughly 1,000 professional categories.

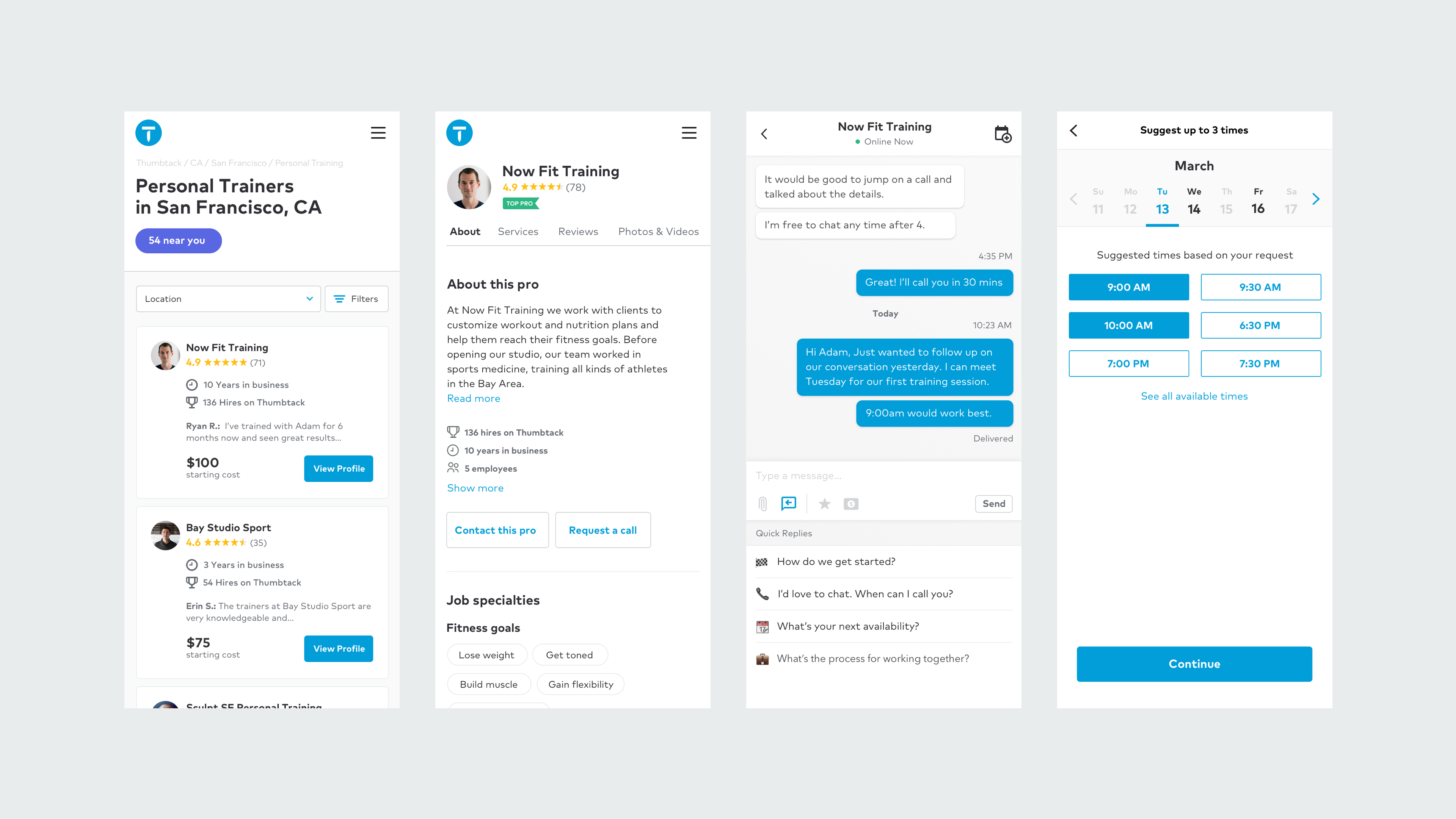

Now, the matching feature is getting an upgrade on the consumer side. Earlier this month the company unveiled Instant Results — a new look for its website and mobile app — that uses all of the data from its 200,000 services professionals to match with the 30 professionals that best correspond to a request for services. It’s among the highest number of professionals listed on any site, according to Zappacosta. The next largest competitor, Yelp, has around 115,000 listings a year. Thumbtack’s professionals are active in a 90 day period.

Filtering by price, location, tools and schedule, anyone in the U.S. can find a service professional for their needs. It’s the culmination of work processing nine years and 25 million requests for services from all of its different categories of jobs.

It’s a long way from the first version of Thumbtack, which had a “buy” tab and a “sell” tab; with the “buy” side to hire local services and the “sell” to offer them.

“From the very early days… the design was to iterate beyond the traditional model of business listing directors. In that, for the consumer to tell us what they were looking for and we would, then, find the right people to connect them to,” said Daniels. “That functionality, the request for quote functionality, was built in from v.1 of the product. If you tried to use it then, it wouldn’t work. There were no businesses on the platform to connect you with. I’m sure there were a million bugs, the UI and UX were a disaster, of course. That was the original version, what I remember of it at least.”

It may have been a disaster, but it was compelling enough to get the company its $1.2 million angel round — enough to barely develop the product. That million dollar investment had to last the company through the nuclear winter of America’s recession years, when venture capital — along with every other investment class — pulled back.

“We were pounding the pavement trying to find somebody to give us money for a Series A round,” Daniels said. “That was a very hard period of the company’s life when we almost went out of business, because nobody would give us money.”

That was a pre-revenue period for the company, which experimented with four revenue streams before settling on the one that worked the best. In the beginning the service was free, and it slowly transitioned to a commission model. Then, eventually, the company moved to a subscription model where service providers would pay the company a certain amount for leads generated off of Thumbtack.

“We weren’t able to close the loop,” Daniels said. “To make commissions work, you have to know who does the job, when, for how much. There are a few possible ways to collect all that information, but the best one, I think, is probably by hosting payments through your platform. We actually built payments into the platform in 2011 or 2012. We had significant transaction volume going through it, but we then decided to rip it out 18 months later, 24 months later, because, I think we had kind of abandoned the hope of making commissions work at that time.”

While Thumbtack was struggling to make its bones, Twitter, Facebook, and Pinterest were raking in cash. The founders thought that they could also access markets in the same way, but investors weren’t interested in a consumer facing business that required transactions — not advertising — to work. User generated content and social media were the rage, but aside from Uber and Lyft the jury was still out on the marketplace model.

“For our company that was not a Facebook or a Twitter or Pinterest, at that time, at least, that we needed revenue to show that we’re going to be able to monetize this,” Daniels said. “We had figured out a way to sign up pros at enormous scale and consumers were coming online, too. That was showing real promise. We said, ‘Man, we’re a hot ticket, we’re going to be able to raise real money.’ Then, for many reasons, our inexperience, our lack of revenue model, probably a bunch of stuff, people were reluctant to give us money.”

The company didn’t focus on revenue models until the fall of 2011, according to Daniels. Then after receiving rejection after rejection the company’s founders began to worry. “We’re like, ‘Oh, shit.’ November of 2009 we start running these tests, to start making money, because we might not be able to raise money here. We need to figure out how to raise cash to pay the bills, soon,” Daniels recalled.

The experience of almost running into the wall put the fear of god into the company. They managed to scrape out an investment from Javelin, but the founders were convinced that they needed to find the right revenue number to make the business work with or without a capital infusion. After a bunch of deliberations, they finally settled on $350,000 as the magic number to remain a going concern.

“That was the metric that we were shooting towards,” said Daniels. “It was during that period that we iterated aggressively through these revenue models, and, ultimately, landed on a paper quote. At the end of that period then Sequoia invested, and suddenly, pros supply and consumer demand and revenue model all came together and like, ‘Oh shit.'”

Finding the right business model was one thing that saved the company from withering on the vine, but another choice was the one that seemed the least logical — the idea that the company should focus on more than just home repairs and services.

The company’s home category had lots of competition with companies who had mastered the art of listing for services on Google and getting results. According to Daniels, the company couldn’t compete at all in the home categories initially.

“It turned out, randomly … we had no idea about this … there was not a similarly well developed or mature events industry,” Daniels said. “We outperformed in events. It was this strategic decision, too, that, on all these 1,000 categories, but it was random, that over the last five years we are the, if not the, certainly one of the leading events service providers in the country. It just happened to be that we … I don’t want to say stumbled into it … but we found these pockets that were less competitive and we could compete in and build a business on.”

The focus on geographical and services breadth — rather than looking at building a business in a single category or in a single geography meant that Zappacosta and company took longer to get their legs under them, but that they had a much wider stance and a much bigger base to tap as they began to grow.

“Because of naivete and this dreamy ambition that we’re going to do it all. It was really nothing more strategic or complicated than that,” said Daniels. “When we chose to go broad, we were wandering the wilderness. We had never done anything like this before.”

From the company’s perspective, there were two things that the outside world (and potential investors) didn’t grasp about its approach. The first was that a perfect product may have been more competitive in a single category, but a good enough product was better than the terrible user experiences that were then on the market. “You can build a big company on this good enough product, which you can then refine over the course of time to be greater and greater,” said Daniels.

The second misunderstanding is that the breadth of the company let it scale the product that being in one category would have never allowed Thumbtack to do. Cross selling and upselling from carpet cleaners to moving services to house cleaners to bounce house rentals for parties — allowed for more repeat use.

More repeat use meant more jobs for services employees at a time when unemployment was still running historically high. Even in 2011, unemployment remained stubbornly high. It wasn’t until 2013 that the jobless numbers began their steady decline.

There’s a question about whether these gig economy jobs can keep up with the changing times. Now, as unemployment has returned to its pre-recession levels, will people want to continue working in roles that don’t offer health insurance or retirement benefits? The answer seems to be “yes” as the Thumbtack platform continues to grow and Uber and Lyft show no signs of slowing down.

“At the time, and it still remains one of my biggest passions, I was interested in how software could create new meaningful ways of working,” said Banister of the Thumbtack deal. “That’s the criteria I was looking for, which is, does this shift how people find work? Because I do believe that we can create jobs and we can create new types of jobs that never existed before with the platforms that we have today.”

May 06, 2018 at 08:06AM