Distributed teams are rewriting the rules of office(less) politics

When we think about designing our dream home, we don’t think of having a thousand roommates in the same room with no doors or walls. Yet in today’s workplace where we spend most of our day, the purveyors of corporate office design insist that tearing down walls and bringing more people closer together in the same physical space will help foster better collaboration while dissolving the friction of traditional hierarchy and office politics.

But what happens when there is no office at all?

This is the reality for Jason Fried, Founder and CEO of Basecamp, and Matt Mullenweg, Founder and CEO of Automattic (makers of WordPress), who both run teams that are 100% distributed across six continents and many time zones. Fried and Mullenweg are the founding fathers of a movement that has inspired at least a dozen other companies to follow suit, including Zapier, Github, and Buffer. Both have either written a book, or have had a book written about them on the topic.

For all of the discussions about how to hire, fire, coordinate, motivate, and retain remote teams though, what is strangely missing is a discussion about how office politics changes when there is no office at all. To that end, I wanted to seek out the experience of these companies and ask: does remote work propagate, mitigate, or change the experience of office politics? What tactics are startups using to combat office politics, and are any of them effective?

“Can we take a step back here?”

Office politics is best described by a simple example. There is a project, with its goals, metrics, and timeline, and then there’s who gets to decide how it’s run, who gets to work on it, and who gets credit for it. The process for deciding this is a messy human one. While we all want to believe that these decisions are merit-based, data-driven, and objective, we all know the reality is very different. As a flood of research shows, they come with the baggage of human bias in perceptions, heuristics, and privilege.

Office politics is the internal maneuvering and positioning to shape these biases and perceptions to achieve a goal or influence a decision. When incentives are aligned, these goals point in same direction as the company. When they don’t, dysfunction ensues.

Perhaps this sounds too Darwinian, but it is a natural and inevitable outcome of being part of any organization where humans make the decisions. There is your work, and then there’s the management of your coworker’s and boss’s perception of your work.

There is no section in your employee handbook that will tell you how to navigate office politics. These are the tacit, unofficial rules that aren’t documented. This could include reworking your wardrobe to match your boss’s style (if you don’t believe me, ask how many people at Facebook own a pair of Nike Frees). Or making time to go to weekly happy hour not because you want to, but because it’s what you were told you needed to do to get ahead.

One of my favorite memes about workplace culture is Sarah Cooper’s “10 Tricks to Appear Smart in Meetings,” which includes…

- Encouraging everyone to “take a step back” and ask “what problem are we really trying to solve”

- Nodding continuously while appearing to take notes

- Stepping out to take an “important phone call”

- Jumping out of your seat to draw a Venn diagram on the whiteboard

Sarah Cooper, The Cooper Review

These cues and signals used in physical workplaces to shape and influence perceptions do not map onto the remote workplace, which gives us a unique opportunity to study how office politics can be different through the lens of the officeless.

Friends without benefits

For employees, the analogy that coworkers are like family is true in one sense — they are the roommates that we never got to choose. Learning to work together is difficult enough, but the physical office layers on the additional challenge of learning to live together. Contrast this with remote workplaces, which Mullenweg of Automattic believes helps alleviate the “cohabitation annoyances” that come with sharing the same space, allowing employees to focus on how to best work with each other, versus how their neighbor “talks too loud on the phone, listens to bad music, or eats smelly food.”

Additionally, remote workplaces free us of the tyranny of the tacit expectations and norms that might not have anything to do with work itself. At an investment bank, everyone knows that analysts come in before the managing director does, and leave after they do. This signals that you’re working hard.

Basecamp’s Fried calls this the “presence prison,” the need to be constantly aware of where your coworkers are and what they are doing at all times, both physically and virtually. And he’s waging a crusade against it, even to the point of removing the green dot on Basecamp’s product. “As a general rule, nobody at Basecamp really knows where anyone else is at any given moment. Are they working? Dunno. Are they taking a break? Dunno. Are they at lunch? Dunno. Are they picking up their kid from school? Dunno. Don’t care.”

There is credible basis for this practice. A study of factory workers by Harvard Business School showed that workers were 10% to 15% more productive when managers weren’t watching. This increase was attributed to giving workers the space and freedom to experiment with different approaches before explaining to managers, versus the control group which tended to follow prescribed instructions under the leery watch of their managers.

Remote workplaces experience a similar phenomenon, but by coincidence. “Working hard” can’t be observed physically so it has to be explained, documented, measured, and shared across the company. Cultural norms are not left to chance, or steered by fear or pressure, which should give individuals the autonomy to focus on the work itself, versus how their work is perceived.

Lastly, while physical workplaces can be the source of meaningful friendships and community, recent research by the Wharton School of Business is just beginning to unravel the complexities behind workplace friendships, which can be fraught with tensions from obligations, reciprocity and allegiances. When conflicts arise, you need to choose between what’s best for the company, and what’s best for your relationship with that person or group. You’re not going to help Bob because your best friend Sally used to date him and he was a dick. Or you’re willing to do anything for Jim because he coaches your kid’s soccer team, and vouched for you to get that promotion.

In remote workplaces, you don’t share the same neighborhood, your kids don’t go to the same school, and you don’t have to worry about which coworkers to invite to dinner parties. Your physical/personal and work communities don’t overlap, which means you (and your company) unintentionally avoid many of the hazards of toxic workplace relationships.

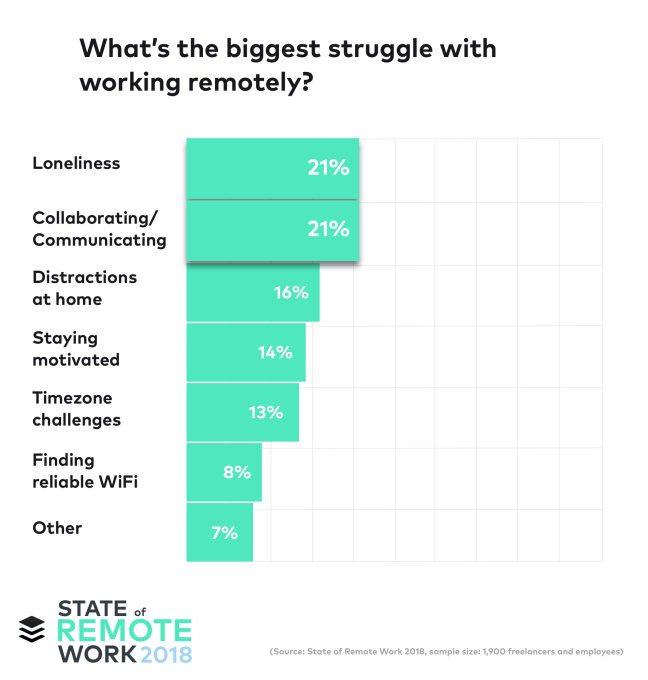

On the other hand, these same relationships can be important to overall employee engagement and well-being. This is evidenced by one of the findings in Buffer’s 2018 State of Remote Work Report, which surveyed over 1900 remote workers around the world. It found that next to collaborating and communicating, loneliness was the biggest struggle for remote workers.

Graph by Buffer (State of Remote Work 2018)

So while you may be able to feel like your own boss and avoid playing office politics in your home office, ultimately being alone may be more challenging than putting on a pair of pants and going to work.

Feature, not a bug?

Physical offices can have workers butting heads with each other. Image by UpperCut Images via Getty Images.

For organizations, the single biggest difference between remote and physical teams is the greater dependence on writing to establish the permanence and portability of organizational culture, norms and habits. Writing is different than speaking because it forces concision, deliberation, and structure, and this impacts how politics plays out in remote teams.

Writing changes the politics of meetings. Every Friday, Zapier employees send out a bulletin with: (1) things I said I’d do this week and their results, (2) other issues that came up, (3) things I’m doing next week. Everyone spends the first 10 minutes of the meeting in silence reading everyone’s updates.

Remote teams practice this context setting out of necessity, but it also provides positive auxiliary benefits of “hearing” from everyone around the table, and not letting meetings default to the loudest or most senior in the room. This practice can be adopted by companies with physical workplaces as well (in fact, Zapier CEO Wade Foster borrowed this from Amazon), but it takes discipline and leadership to change behavior, particularly when it is much easier for everyone to just show up like they’re used to.

Writing changes the politics of information sharing and transparency. At Basecamp, there are no all-hands or town hall meetings. All updates, decisions, and subsequent discussions are posted publicly to the entire company. For companies, this is pretty bold. It’s like having a Facebook wall with all your friends chiming in on your questionable decisions of the distant past that you can’t erase. But the beauty is that there is now a body of written decisions and discussions that serves as a rich and permanent artifact of institutional knowledge, accessible to anyone in the company. Documenting major decisions in writing depoliticizes access to information.

Remote workplaces are not without their challenges. Even though communication can be asynchronous through writing, leadership is not. Maintaining an apolitical culture (or any culture) requires a real-time feedback loop of not only what is said, but what is done, and how it’s done. Leaders lead by example in how they speak, act, and make decisions. This is much harder in a remote setting.

A designer from WordPress notes the interpersonal challenges of leading a remote team. “I can’t always see my teammates’ faces when I deliver instructions, feedback, or design criticism. I can’t always tell how they feel. It’s difficult to know if someone is having a bad day or a bad week.”

Zapier’s Foster is also well aware of these challenges in interpersonal dynamics. In fact, he has written a 200-page manifesto on how to run remote teams, where he has an entire section devoted to coaching teammates on how to meet each other for the first time. “Because we’re wired to look for threats in any new situation… try to limit phone or video calls to 15 minutes.” Or “listen without interrupting or sharing your own stories.” And to “ask short, open ended questions.” For anyone looking for a grade school refresher on how to make new friends, Wade Foster is the Dale Carnegie of the remote workforce.

To office, or not to office

What we learn from companies like Basecamp, Automattic, and Zapier is that closer proximity is not the antidote for office politics, and certainly not the quick fix for a healthy, productive culture.

Maintaining a healthy culture takes work, with deliberate processes and planning. Remote teams have to work harder to design and maintain these processes because they don’t have the luxury of assuming shared context through a physical workspace.

The result is a wealth of new ideas for a healthier, less political culture — being thoughtful about when to bring people together, and when to give people their time apart (ending the presence prison), or when to speak, and when to read and write (to democratize meetings). It seems that remote teams have largely succeeded in turning a bug into a feature. For any company still considering tearing down those office walls and doors, it’s time to pay attention to the lessons of the officeless.

Logging you in...

Logging you in...