D-Wave offers the first public access to a quantum computer

Outside the crop of construction cranes that now dot Vancouver’s bright, downtown greenways, in a suburban business park that reminds you more of dentists and tax preparers, is a small office building belonging to D-Wave. This office — squat, angular and sun-dappled one recent cool Autumn morning — is unique in that it contains an infinite collection of parallel universes.

Founded in 1999 by Geordie Rose, D-Wave worked in relative obscurity on esoteric problems associated with quantum computing. When Rose was a PhD student at the University of British Columbia, he turned in an assignment that outlined a quantum computing company. His entrepreneurship teacher at the time, Haig Farris, found the young physicists ideas compelling enough to give him $1,000 to buy a computer and a printer to type up a business plan.

The company consulted with academics until 2005, when Rose and his team decided to focus on building usable quantum computers. The result, the Orion, launched in 2007, and was used to classify drug molecules and play Sodoku. The business now sells computers for up to $10 million to clients like Google, Microsoft and Northrop Grumman.

“We’ve been focused on making quantum computing practical since day one. In 2010 we started offering remote cloud access to customers and today, we have 100 early applications running on our computers (70 percent of which were built in the cloud),” said CEO Vern Brownell. “Through this work, our customers have told us it takes more than just access to real quantum hardware to benefit from quantum computing. In order to build a true quantum ecosystem, millions of developers need the access and tools to get started with quantum.”

Now their computers are simulating weather patterns and tsunamis, optimizing hotel ad displays, solving complex network problems and, thanks to a new, open-source platform, could help you ride the quantum wave of computer programming.

Inside the box

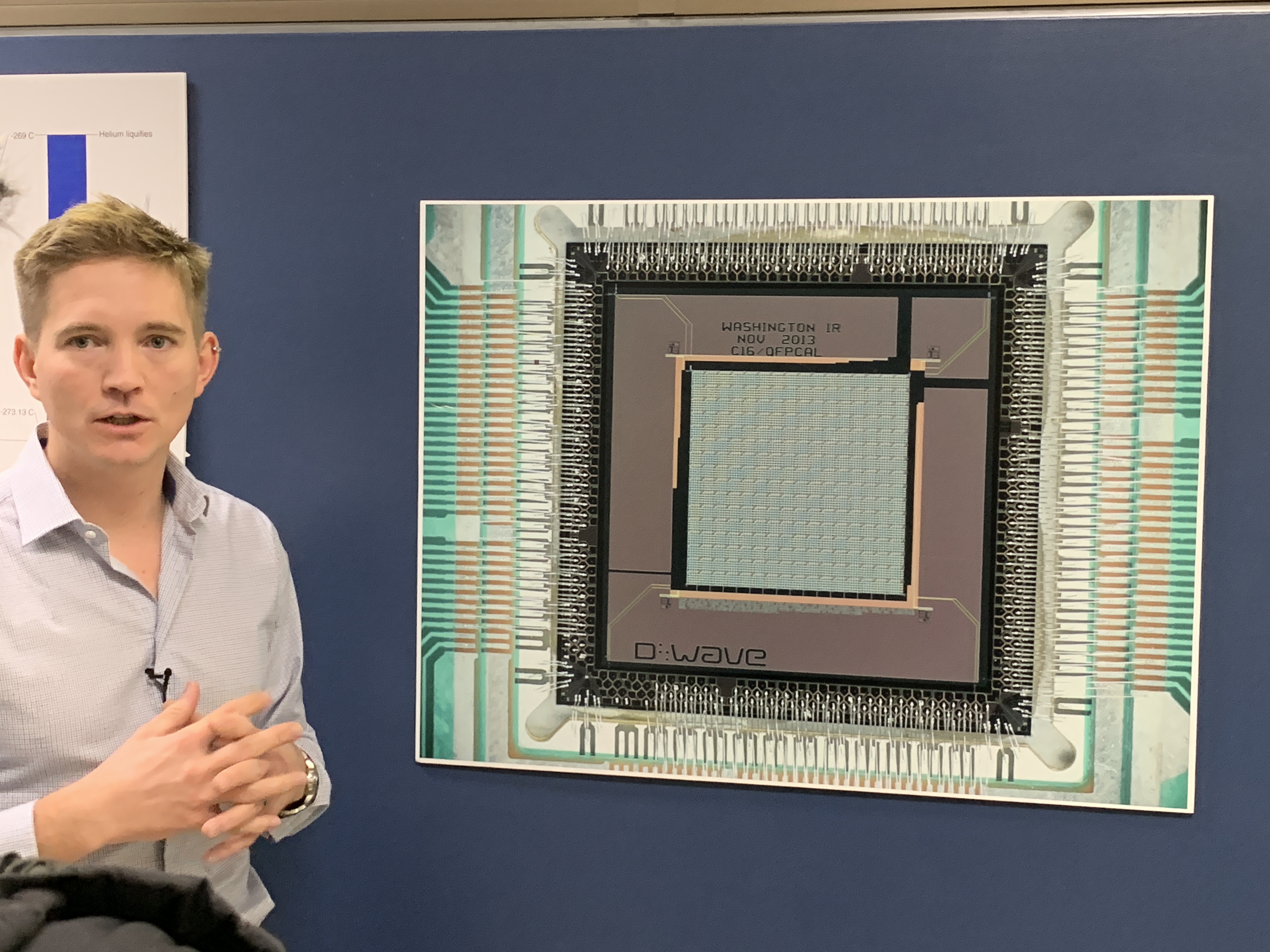

When I went to visit D-Wave they gave us unprecedented access to the inside of one of their quantum machines. The computers, which are about the size of a garden shed, have a control unit on the front that manages the temperature as well as queuing system to translate and communicate the problems sent in by users.

Inside the machine is a tube that, when fully operational, contains a small chip super-cooled to 0.015 Kelvin, or -459.643 degrees Fahrenheit or -273.135 degrees Celsius. The entire system looks like something out of the Death Star — a cylinder of pure data that the heroes must access by walking through a little door in the side of a jet-black cube.

It’s quite thrilling to see this odd little chip inside its super-cooled home. As the computer revolution maintained its predilection toward room-temperature chips, these odd and unique machines are a connection to an alternate timeline where physics is wrestled into submission in order to do some truly remarkable things.

And now anyone — from kids to PhDs to everyone in-between — can try it.

Into the ocean

Learning to program a quantum computer takes time. Because the processor doesn’t work like a classic universal computer, you have to train the chip to perform simple functions that your own cellphone can do in seconds. However, in some cases, researchers have found the chips can outperform classic computers by 3,600 times. This trade-off — the movement from the known to the unknown — is why D-Wave exposed their product to the world.

“We built Leap to give millions of developers access to quantum computing. We built the first quantum application environment so any software developer interested in quantum computing can start writing and running applications — you don’t need deep quantum knowledge to get started. If you know Python, you can build applications on Leap,” said Brownell.

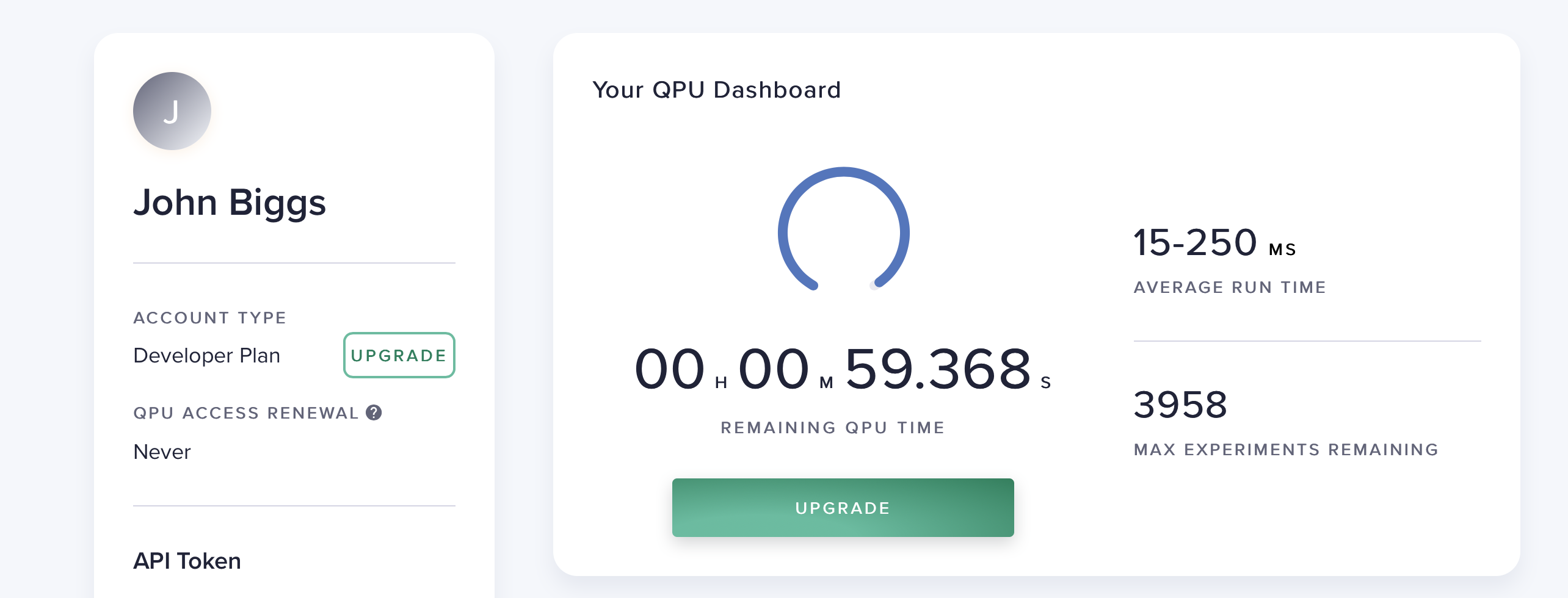

To get started on the road to quantum computing, D-Wave built the Leap platform. The Leap is an open-source toolkit for developers. When you sign up you receive one minute’s worth of quantum processing unit time which, given that most problems run in milliseconds, is more than enough to begin experimenting. A queue manager lines up your code and runs it in the order received and the answers are spit out almost instantly.

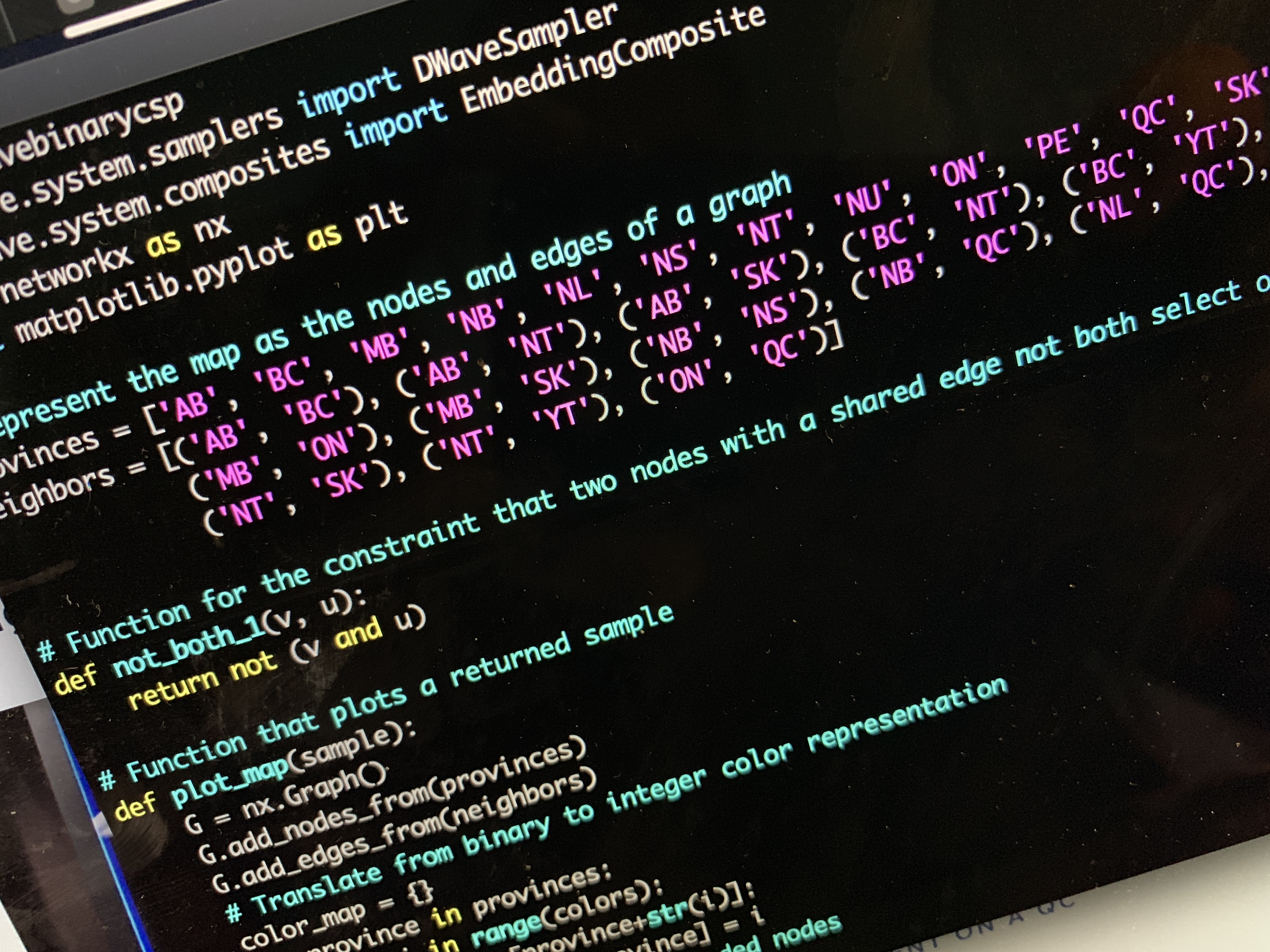

You can code on the QPU with Python or via Jupiter notebooks, and it allows you to connect to the QPU with an API token. After writing your code, you can send commands directly to the QPU and then output the results. The programs are currently pretty esoteric and require a basic knowledge of quantum programming but, it should be remembered, classic computer programming was once daunting to the average user.

I downloaded and ran most of the demonstrations without a hitch. These demonstrations — factoring programs, network generators and the like — essentially turned the concepts of classical programming into quantum questions. Instead of iterating through a list of factors, for example, the quantum computer creates a “parallel universe” of answers and then collapses each one until it finds the right answer. If this sounds odd it’s because it is. The researchers at D-Wave argue all the time about how to imagine a quantum computer’s various processes. One camp sees the physical implementation of a quantum computer to be simply a faster methodology for rendering answers. The other camp, itself aligned with Professor David Deutsch’s ideas presented in The Beginning of Infinity, sees the sheer number of possible permutations a quantum computer can traverse as evidence of parallel universes.

What does the code look like? It’s hard to read without understanding the basics, a fact that D-Wave engineers factored for in offering online documentation. For example, below is most of the factoring code for one of their demo programs, a bit of code that can be reduced to about five lines on a classical computer. However, when this function uses a quantum processor, the entire process takes milliseconds versus minutes or hours.

Classical

# Python Program to find the factors of a number

define a function

def print_factors(x):

This function takes a number and prints the factors

print(“The factors of”,x,”are:”)

for i in range(1, x + 1):

if x % i == 0:

print(i)

change this value for a different result.

num = 320

uncomment the following line to take input from the user

#num = int(input(“Enter a number: “))

print_factors(num)

Quantum

@qpu_ha

def factor(P, use_saved_embedding=True):

####################################################################################################

get circuit

####################################################################################################

construction_start_time = time.time()

validate_input(P, range(2 ** 6))

get constraint satisfaction problem

csp = dbc.factories.multiplication_circuit(3)

get binary quadratic model

bqm = dbc.stitch(csp, min_classical_gap=.1)

we know that multiplication_circuit() has created these variables

p_vars = [‘p0’, ‘p1’, ‘p2’, ‘p3’, ‘p4’, ‘p5’]

convert P from decimal to binary

fixed_variables = dict(zip(reversed(p_vars), “{:06b}”.format(P)))

fixed_variables = {var: int(x) for(var, x) in fixed_variables.items()}

fix product qubits

for var, value in fixed_variables.items():

bqm.fix_variable(var, value)

log.debug(‘bqm construction time: %s’, time.time() – construction_start_time)

####################################################################################################

run problem

####################################################################################################

sample_time = time.time()

get QPU sampler

sampler = DWaveSampler(solver_features=dict(online=True, name=’DW_2000Q.*’))

_, target_edgelist, target_adjacency = sampler.structure

if use_saved_embedding:

load a pre-calculated embedding

from factoring.embedding import embeddings

embedding = embeddings[sampler.solver.id]

else:

get the embedding

embedding = minorminer.find_embedding(bqm.quadratic, target_edgelist)

if bqm and not embedding:

raise ValueError(“no embedding found”)

apply the embedding to the given problem to map it to the sampler

bqm_embedded = dimod.embed_bqm(bqm, embedding, target_adjacency, 3.0)

draw samples from the QPU

kwargs = {}

if ‘num_reads’ in sampler.parameters:

kwargs[‘num_reads’] = 50

if ‘answer_mode’ in sampler.parameters:

kwargs[‘answer_mode’] = ‘histogram’

response = sampler.sample(bqm_embedded, **kwargs)

convert back to the original problem space

response = dimod.unembed_response(response, embedding, source_bqm=bqm)

sampler.client.close()

log.debug(’embedding and sampling time: %s’, time.time() – sample_time)

“The industry is at an inflection point and we’ve moved beyond the theoretical, and into the practical era of quantum applications. It’s time to open this up to more smart, curious developers so they can build the first quantum killer app. Leap’s combination of immediate access to live quantum computers, along with tools, resources, and a community, will fuel that,” said Brownell. “For Leap’s future, we see millions of developers using this to share ideas, learn from each other and contribute open-source code. It’s that kind of collaborative developer community that we think will lead us to the first quantum killer app.”

The folks at D-Wave created a number of tutorials as well as a forum where users can learn and ask questions. The entire project is truly the first of its kind and promises unprecedented access to what amounts to the foreseeable future of computing. I’ve seen lots of technology over the years, and nothing quite replicated the strange frisson associated with plugging into a quantum computer. Like the teletype and green-screen terminals used by the early hackers like Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak, D-Wave has opened up a strange new world. How we explore it us up to us.