Adobe XD’s Trajectory Paints a Picture of Enterprise Innovation

When it comes to ubiquity within the software world, there are a few names that top the list: Microsoft, Google, Adobe and others. But what happens when one of those companies releases a new product and tries to corner a market they have never entered before? It becomes a test of resource allocation, industry knowledge, and, above all, the ability to drive innovation in a field already guided by top-tier innovators.

Adobe put themselves to that test with 2017’s release of Adobe XD, which is user experience (UX) design software that sought to compete with the likes of Sketch and Zeplin, which are the current industry-leading UX software offerings. Adobe sets the pace the on almost all of the other types of software fields they dabble in; think of Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, Premiere Pro and more. But with XD, the California company had to build something from the ground up with the goal of competing in an already crowded field.

The company’s annual conference, Adobe MAX, took place last month and featured several updates to XD. But unlike users of Adobe’s other programs, XD users have become accustomed to regular upgrades. XD adheres to a very rigorous update period, releasing patches, features and small tweaks on a monthly basis, something Adobe very rarely does with their other products. October’s releases were, of course, a bit bulkier, considering they coincided with the MAX conference: new features involving voice prototyping, animation support, and third-party plug-ins headlined the update.

Presenting Adobe XD updates at MAX 2018.

Even though the upgrades are plentiful and the software is powerful, the journey of Adobe XD is fascinating. The software giant is trying to enter a new market and not only build a competitor but become a leader in the space. This results in some really interesting discussions around decision-making and resourcefulness as the XD team looks to not only build a product that works but also one that fixes the problems they see within the industry on a daily basis.

When XD first released, a common thought from UX designers was, “this is interesting, but it’s not there quite yet.” Cisco Guzman, the director of product management for XD, recognized this as less of a problem and more of an inspiration.

“The general consensus was that, XD is promising, and that XD seems really great, and I wish I could use it,” he explains. “Customers were saying, ‘this could be something.’ But the thing we’re excited about is that we’re not just trying to fill the product with stuff. We’re trying to give people a different way of doing their work. We’ve come a long way in this last year.”

The goal for Guzman and the XD team was simple. Designers are used to working in a specific pattern, so XD had to offer a space where they can design, prototype, and share, all in one piece of software. Beyond that, the team had to innovate and see what kinds of features they could add to elevate XD beyond a normal UX solution.

It is that kind of ambition that defines Adobe’s endeavour to enter a new industry. The company is massive and boasts a firm hold on their other projects’ fields, so when it comes to product development, the teams behind the new software can afford to be ambitious—and when ambition mixes with a strong depth of talent and a seemingly unlimited pool of resources, good things happen. At least that was the plan for Guzman and the XD team, considering they were able to let the culture of design guide them, rather than strict usage quotas or arbitrary financial goals.

“In order to stay focused on delivering product that is elegant and that does the job, I have to not be overly focused on competition, the market, and what we have to do,” says Guzman. “I just think about how soon we can stop designers from wasting their time. I think of it like, this is a couple more designers we got to keep in the trade for a year.”

“Culture is our most important resource,” Guzman continues. “We love designers, so we act in ways that show that, and the number one way to do that is solving their problems.”

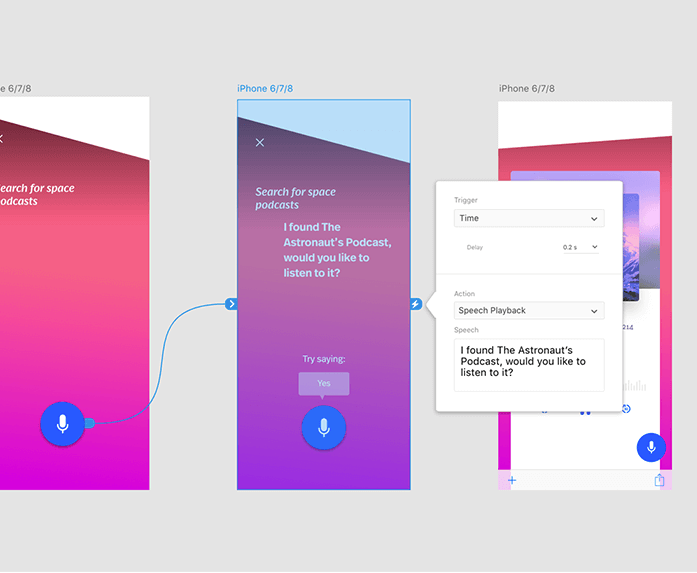

Solving problems is great, but a goal for Adobe has always been to solve problems people never knew they really had. This means bringing in new concepts or innovations and familiarizing users with them before they hit the mainstream. One of XD’s core updates shown at MAX does precisely that. Voice prototyping means UX designers can create triggers launched by a particular word or phrase (more in the video below). XD allows designers to access a powerful text-to-speech engine so they can incorporate the quickly growing medium into whatever app or platform they are creating, something relatively unheard of in the industry.

A big part of creating voice prototyping for XD came from Adobe’s acquisition of Sayspring in April this year. Sayspring focused on building Google and Alexa voice prototyping solutions for clients, so the move to bring them into the Adobe team and help with voice was natural. For Sayspring, this was an exciting move to join an enterprise such as Adobe, but also to have the chance to work on something completely new.

“Because XD wasn’t a legacy product and it was built from the ground up, it was just good software to come into and work on,” says Mark Webster, the CEO and founder of Sayspring. “We built all the web features, and the Windows and Mac features, so that is a testament to the workflow and principles at Adobe.”

The schedule of updates for XD also guided the workflow for Guzman, Webster, and the rest of the team. The monthly updates brought a sense of collaboration and feedback to XD, an integral factor when entering a new market.

“It’s about the relationship. Designers these days expect a direct relationship between a problem they’re having and that fix actually coming,” says Guzman. He laughs and recalls the old days of physical Adobe products. “When we were saving up our $1,200 every two years to buy a box of software, it was a different relationship.”

Despite the rigorous and exhaustive schedule of monthly updates and fixes, there is a silver lining, and it goes back to why Guzman works on the software in the first place: culture. Every day, he and the team can show up and build something that will solve problems, and actually see those solutions get shipped with a quick timeline. That same kind of mentality drove the Sayspring team to become quick learners.

Normally, Adobe would give an acquisition some time—maybe a year—to settle in and integrate their services to the company. With Sayspring, Adobe executives only expected the company to demo Voice at MAX, then ship in Q4.

“We said there’s no way we’re not shipping at MAX. We’ll make this happen,” says Webster. “Coming out of the startup environment, we love that hustle. We have ambitious plans and we want to push this stuff out. The last thing we want to be is an innovation team—we want to ship.”

An example of voice prototyping in Adobe XD.

Even as a five-person team being acquired by a software behemoth, the agile pace of things helped make Sayspring feel at home.

“XD was released as an early project, then only launched 1.0 last year. After that, 60 new features and monthly releases,” says Webster, explaining the quick pace of development. “Companies like Adobe, you would think they don’t deliver and move like that, but XD does. It was exciting for us to come into a place where there was that same hustle and passion we felt for getting things out the door that you typically have in a startup, in this kind of environment.”

With XD and voice prototyping, Adobe has a chance to really help define how a new medium of interaction evolves. Well, not Adobe themselves, but moreso the community that will interact with voice every day. This is the guiding culture that Guzman mentions—the ability to go to work everyday and help bring a new industry to life.

“Designers having access to a new medium is wildly exciting,” says Webster. “I think for voice to mature as an interface, it needs the creative community to define all the UX convention around it.”

“When you build a mobile app, we have hamburger menus, pull down to refresh, and tons of stuff to rely on—but what is voice? In order for that to be established, the community needs access. We see this feature both helping those currently working with voice today access better tools, but then also allowing the creative community to get involved and define it.”

In that vein, XD has already seen some odd interactions that will soon be streamlined as more people add voice to their design arsenal. Early users of XD’s voice prototyping have been mapping out interactive voice response within their apps, which essentially means asking users to “say 1 for yes, say 2 for no.” This is a poor use of the software considering the current capabilities of virtual assistants, but Webster outlines that example of a way people are introducing themselves to the software and learning how they can get better with it over time.

If someone were to look at XD as a standalone product made by a new company, they may say it is an ambitious competitor trying to enter a saturated market. But when Adobe releases a product like XD, it becomes a case study in enterprise product discovery and the ability to remain agile in a culture of deliberate innovation. XD may have a bit to go if it plans on being the market leader, but the current product roadmap illustrates a company willing to shed its traditional growth patterns and take a risk by listening to what their user base actually wants.