Younger consumers adopt voice technology faster, but use voice assistants less, report claims

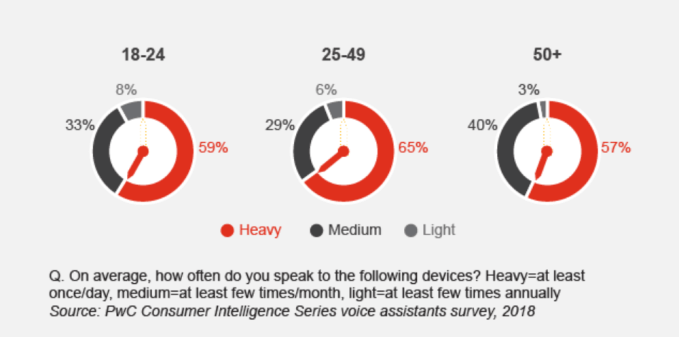

Here’s an odd juxtaposition for you. According to a new report on voice assistants released today by PwC, younger users are adopting voice technology at a faster rate than their older counterparts, but are somehow using their voice assistants less often. The report found that users 18 through 24 had fewer “heavy” users of voice technology, compared with those 25 to 49, and 50 or older.

The study also found that 8 percent of the youngest demographic said they only used a voice assistant a few times per year, compared with 6 percent of those 25 to 49, and only 3 percent of those 50 and up.

That’s an interesting finding, if accurate, given that younger users tend to be not only those who adopt technology at a quicker pace than older people, but who use it more frequently, as well.

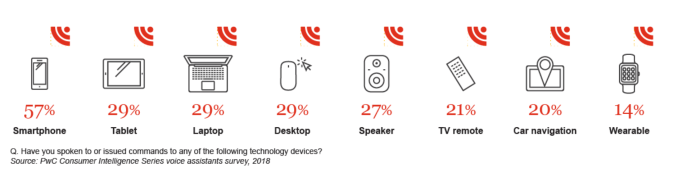

And the issue isn’t one of general awareness it seems. Adoption of voice technology across platforms – including phones, tablets, computers, speakers, wearables, TV remotes and cars – is being driven by younger consumers, says PwC, along with households with children, and those households with incomes of over $100,000.

In addition, while the majority of those 18 to 24 say they use their voice assistant the same (22%) or more (55%) than they did when they first started, a sizable 23 percent said they use it less often.

On the smartphone, 16 percent of all users said they use it less often, and on speaker devices, like Amazon Echo, 12 percent said they use it less often. The flip side of this finding is that speakers are actually doing better than smartphones in terms of increased usage of voice over time. 61 percent said they’re using their voice speakers more since they started, while only 52 percent say they use their smartphone voice assistant more.

So if not familiarity or adoption, what’s causing the youngest users to limit the time they spend using voice? The report claims it’s basically an image thing.

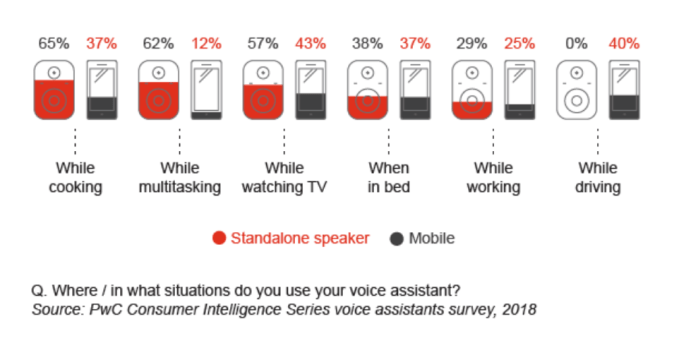

That is, younger users prefer to use voice technology in private instead of in public. They said that using voice assistants in public “just looks weird.” And because younger users likely spend more time outside the home, they end up using voice assistants less.

This has led to a situation where the youngest users are taking advantage of voice assistants less frequently on a daily basis. 59 percent of 18 to 24 year olds speak to a voice assistant at least once per day, compared with 65 percent of 25 to 49 year olds.

But young users aren’t alone in their preference for using voice in private. Overall, the majority of people (74%) are regularly using voice technology in the home, while cooking, multitasking, watching TV, and lounging in bed, for example.

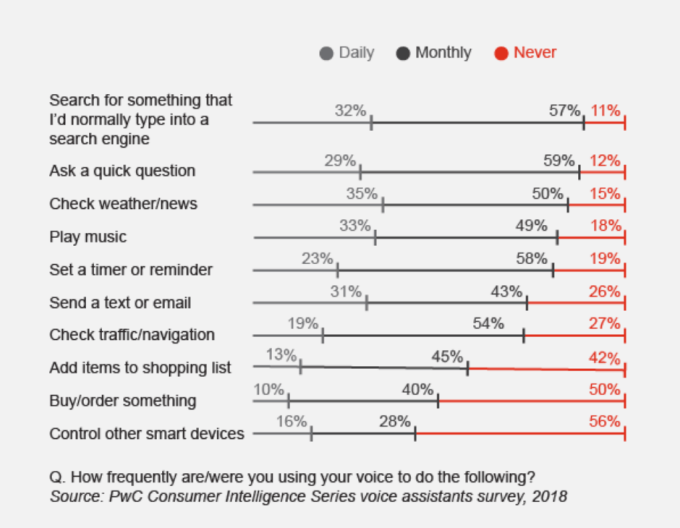

And despite the advances in voice assistant’s capabilities – playing games, using voice apps, shopping, or offering smart home control – the majority of consumers are still using them for basic tasks like checking the weather or news, playing music, and searching for something that would normally be typed into a search engine.

There are still some barriers to the adoption of voice technology, however, including consumer’s concerns that assistants are growing too complex or expensive, a limited understand of what to do with voice devices, and lack of trust.

In fact, 38 percent said they wouldn’t want something “listening in” on their life all the time, which is what people believe adding a voice device to their home implies.

Largely, trust was a concern in other areas, too – with people not trusting the voice device to process a shopping order correctly, concerned about the security of payments through voice, or worried that their kids would figure out a way to order items without approval. (Alexa devices faced this issue at first, but Amazon has since built in purchase controls.)

Generally, the consumer experience of using voice seems to be well-received by most, but voice assistant technology makers will do well to learn from social media’s user privacy debacles, and take steps to protect consumer privacy, not sell data, and refrain from being “creepy,” PwC suggests.