The innovation supply chain: How ideas traverse continents and transform economies

While Westerners often associate the invention of calculus with 17th century European luminaries like Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, its theoretical foundations actually stretch back millennia. Fundamental theorems appear in ancient Egyptian work from 1820 BC, and later influences sprout from Babylonian, Ancient Greek, Chinese and Middle Eastern texts.

Such is the nature of the world’s biggest ideas — concepts that arise in one corner of the world provide the scaffolding for future advancements. Realizing the true potential of any idea takes time and requires input from diverse cultures and perspectives.

Technological innovation is no exception.

In the tech world today, this is playing out in three important ways:

- ideas improve when they become global;

- the best ideas are increasingly starting internationally; and

- testing globally is a differentiated strategy.

Ideas improve as they scale globally

Like calculus, technological innovation benefits from international iteration.

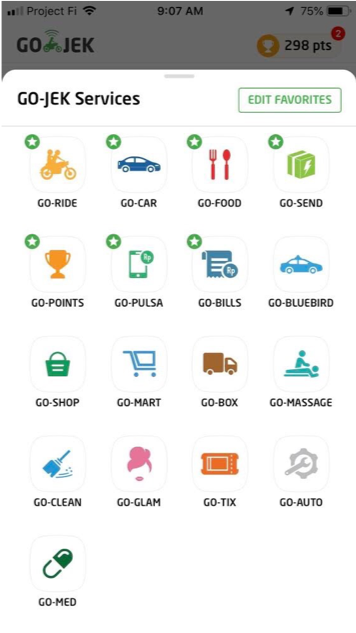

Ridesharing, for instance, started as an innovation pioneered by Uber and Lyft in San Francisco. Yet startups rapidly exported the model globally. Such evolution reflects local needs. Take Go-Jek, a ridesharing app that is now a dominant local player in Indonesia. Although Go-Jek “replicated” the model, they also took a highly localized approach, applying the Uber/Lyft concept to Jakarta’s existing informal system of motorcycle taxis, “ojeks.”

Yet Go-Jek realized that ojek drivers had the potential to do so much more than just move people around. The company aims to maximize driver engagement throughout the day and has built a multi-service app that allows them to not only transport people, but also deliver food, packages and services. As Nadiem Makarim, Go-Jek’s CEO put it, “In the mornings, we drive people from home to work. At lunch, we deliver them meals to the office. In the late afternoon, we drive people back home. In the evenings, we deliver ingredients and meals. And in-between all this, we deliver e-commerce, financial products and other services.”

Silicon Valley used to have a monopoly on the idea, manufacturing and distribution of innovation. No longer.

The model of leveraging a single ridesharing platform to deliver a range of services is undoubtedly different from the Silicon Valley original. In Silicon Valley, an array of companies offering Uber for X have sprung up, yet some of Uber’s latest product categories — like UberEats — seem more akin to the Southeast Asian model.

Tellingly, Go-Jek’s vision incorporates inspiration from another geography: China. In China, platforms like Tencent’s WeChat offer a range of direct and third-party services spanning ride-hailing, shopping, food delivery and, of course, payments. WeChat payment functionality (like Ant’s equivalent) is nearly ubiquitous in major Chinese cities.

Go-Jek, like its competitor Grab, has evolved its model to include a payments platform as part of the app. It is striking to see Uber enter financial services, as well — take, for example, the recent Uber credit card.

These models evolve by learning and combining lessons from other geographies.

The seeds are increasingly global

Historically, entrepreneurs outside Silicon Valley were accused of being replicators — copying and adapting successful models pioneered in San Francisco or Palo Alto.

Times are changing.

Many of the most compelling tech innovations increasingly come from outside of Silicon Valley, and even the United States. Just look at some of 2018’s most successful IPOs — Sweden’s Spotify, Brazil’s Stone and China’s PinDuoDuo (a Cathay Innovation portfolio company).

Entrepreneurs are working to replicate innovations from every corner of the globe. Take mobile payments. M-Pesa, Kenya’s ubiquitous payments platform that now transacts a remarkable 50 percent of its country’s GDP, has created a global movement. Today, there are more than 275 deployments around the world.

Certain geographies are specializing. Toronto and Montreal are emerging as artificial intelligence hubs. London and Singapore remain leading fintech hubs. Israel is known for its cybersecurity and analytics expertise. And regionally focused initiatives are catalyzing this further. For instance, Rise of the Rest is committed to supporting entrepreneurs across the U.S., and organizations like Endeavor facilitate the development of entrepreneurial hubs worldwide.

The nascent innovation supply chain will see increasing globalization of the generation of new ideas.

Emerging ecosystems can provide optimal testing grounds

Broadway is famous for testing its shows in smaller markets before committing them to the big stage. Similarly, innovators are looking to emerging markets to test models before scaling them.

SkyAlert, which operates an earthquake early warning system, is an illustrative example. In most earthquakes, people do not die from the shakes but rather from getting trapped or crushed under collapsing buildings. Technologically, it is possible to perceive and distribute an early warning, as a quake is first felt near the epicenter and travels outward from there. Through its network of distributed sensors, SkyAlert promises its users a head start to evacuate buildings, and can work with companies to automate security protocols (e.g. gas shutoff).

SkyAlert was not born in San Francisco. Alejandro Cantu, SkyAlert’s founder, began in Mexico City, which he describes as his innovation laboratory. The early versions were focused on R&D rather than commercialization. Developing this in Mexico City was much more affordable for product innovation. Salaries were cheaper. Cost of acquisition was cheaper. The U.S. is now his main target market, but Mexico served as his early base of operations and testing ground.

As a community of innovators, we have an opportunity to take advantage of these trends.

Just as most Silicon Valley techies are familiar with the buzz around Amazon’s home drone deliveries, the majority remain unaware that some of the most interesting drone innovation is happening far away in emerging markets. In developing nations, where infrastructure is far more limited, drones offer lifesaving potential. Startups like Zipline leverage drones to leapfrog broken or nonexistent infrastructure. They deliver time-sensitive drugs and blood across Rwanda through a partnership with the ministry of health. Already, its drones have covered 600,000 km and delivered nearly 14,000 units of blood (one-third of which were in emergency situations).

Entrepreneurs are testing these innovations in markets that are more affordable, and where the need is most acute. Over time, such models will scale and return to developed markets. This is how the innovation supply chain will evolve.

Where we go from here

The Economist recently predicted a “Techodus” — that innovation will continue to shift away from Silicon Valley. The story is more nuanced.

Silicon Valley used to have a monopoly on the idea, manufacturing and distribution of innovation. No longer. The creative spark is coming from everywhere, innovators are testing ideas in markets where costs are lower and needs are more acute and models are perfected from lessons from around the world.

As a community of innovators, we have an opportunity to take advantage of these trends. You have a new product idea that could be completely transformative? Great. Who else is doing that globally? You want to test a new idea? What are the advantages and disadvantages of various locations? How can the innovations’ lessons from abroad be replicated locally?